Analyzing public company financial statements supports financial models, mergers and acquisitions, and capital-raising efforts. These statements help investment banking analysts reveal key insights into a company’s profitability, liquidity, and financial health, guiding strategic decisions. For example, in Amazon’s acquisition of Whole Foods, Amazon reviewed Whole Foods’ financials to ensure the deal aligned with its long-term goals.

Metrics like earnings per share (EPS), return on equity (ROE), and free cash flow (FCF) help analysts value companies and predict performance, while financial ratios assess solvency and liquidity to optimize capital structures.

Key Takeaways:

- Comprehensive financial statement analysis supports complex financial modeling, M&A, and capital-raising efforts.

- Metrics like EPS, ROE, and FCF provide accurate valuations and future performance forecasts.

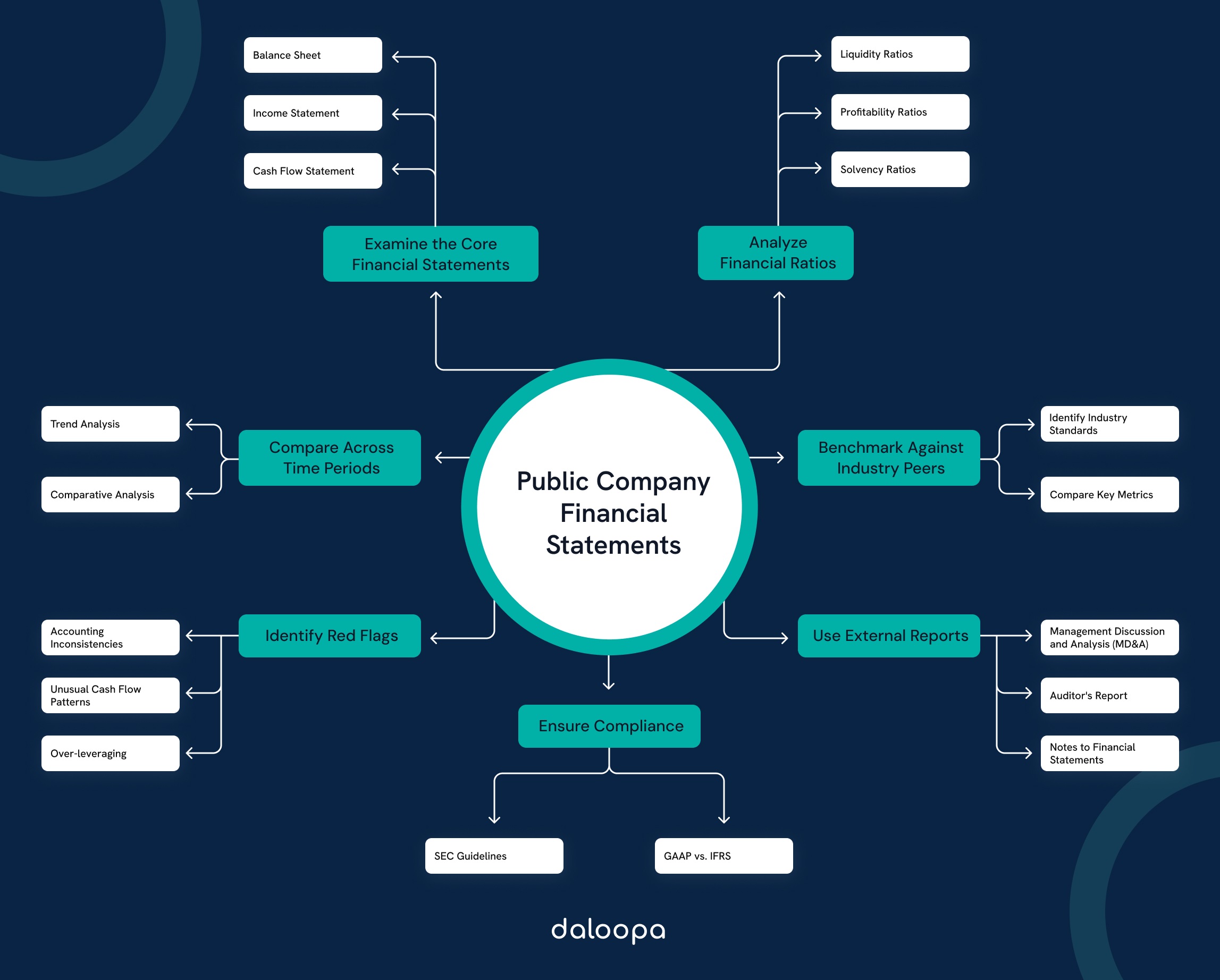

- The process of analyzing corporate reports fall into main categories:

- Financial Statements and Public Companies

- The Balance Sheet Explained

- Income Statement Insights

- Advanced Cash Flow Statement Analysis

- Equity and Earnings Per Share

- Accounting Principles and Standards

- Financial Statement Presentation and Analysis

- Detailed Analysis of Financial Statements

- Practical Applications

- Empowering Bank Investment Analysts

Financial Statements and Public Companies

Public companies must comply with stringent regulatory frameworks when preparing financial statements, ensuring transparency and fostering investor confidence. These regulations govern how companies report their financial health, helping investors and analysts make informed decisions. Key financial statements such as the balance sheet, income statement, and cash flow statement provide a comprehensive overview of a company’s financial performance and position.

Key Financial Statements:

- Balance Sheet: Reflects assets, liabilities, and shareholders’ equity, providing insights into a company’s financial structure.

- Income Statement: Shows revenue, expenses, and profit, revealing a company’s profitability over a specific period.

- Cash Flow Statement: Details cash inflows and outflows, illustrating liquidity and cash management capabilities.

These reports are typically released quarterly and annually, offering stakeholders consistent updates. However, beyond the basics, regulatory frameworks like the Sarbanes-Oxley Act (SOX) and International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS 9) profoundly impact how financial data is presented, ensuring both accuracy and accountability in public company reporting.

Impact of Regulatory Compliance

The Sarbanes-Oxley Act, enacted in response to corporate scandals like Enron, revolutionized financial reporting by enforcing stricter internal controls and auditor independence. SOX has significantly increased compliance costs and led to more reliable financial disclosures. For instance, General Electric (GE) faced a sharp valuation decline when accounting issues emerged in 2018, resulting in hefty fines and the requirement to overhaul its reporting processes to ensure compliance with SOX regulations.

Similarly, IFRS 9, which deals with financial instruments, introduced changes in how companies recognize and measure credit losses, impacting industries heavily reliant on financial assets, such as banking. HSBC and Deutsche Bank saw substantial changes in their provisioning models due to the new rules on expected credit losses, significantly affecting their profitability metrics.

Recent Debates and Changes in Accounting Standards

Recent shifts in accounting standards continue to shape financial reporting practices. For example, the debate around IFRS vs. U.S. GAAP convergence has intensified, with some advocating for global standardization to simplify cross-border investments. However, differences remain, particularly in revenue recognition and lease accounting, which affect how companies report profits and liabilities. For instance, Airlines like Delta and American Airlines experienced notable changes in their balance sheets after adopting IFRS 16, which reclassified leases, substantially increasing reported liabilities and altering debt ratios.

Moreover, evolving regulations such as environmental, social, and governance (ESG) reporting are now being considered in financial statements, reflecting the growing importance of sustainability in corporate performance metrics. Regulatory bodies like the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) are currently evaluating how to incorporate ESG disclosures, which will further impact how companies report on non-financial metrics like carbon emissions and labor practices.

Importance of Compliance and Accuracy

Failure to comply with these regulations not only results in legal consequences but can also lead to deterioration in investor trust. For example, Tesla faced scrutiny from the SEC regarding its accounting for revenue and profit projections in recent years, creating market volatility and raising concerns about transparency, highlighting the reputational risks of non-compliance and inaccurate reporting.

By adhering to these regulatory frameworks and staying updated with changes in standards, companies ensure the integrity of their financial statements. Investors and analysts depend on this transparency to evaluate stock prices, assess risks, and make well-informed investment decisions.

The Balance Sheet Explained

The balance sheet offers a comprehensive snapshot of a company’s financial position, detailing its assets, liabilities, and shareholder equity. Financial analysts use balance sheets to assess a firm’s leverage and liquidity risks, providing insights into its ability to manage debt and meet short-term obligations.

Assets, Liabilities, and Shareholder Equity

- Assets: Assets represent resources owned by the company that have economic value. They are divided into current assets—such as cash, inventory, and accounts receivable, which can be converted into cash within a year—and non-current assets, which include long-term investments like property, equipment, and intellectual property. Capital-intensive industries, like manufacturing or energy, typically have significant non-current assets such as heavy machinery or infrastructure, whereas tech companies may have a higher proportion of intangible assets like software or intellectual property.

- Liabilities: Liabilities represent obligations the company owes to others. These are split into current liabilities, due within a year, and long-term liabilities, payable over a longer period. Analysts pay close attention to current liabilities (e.g., short-term debt, accounts payable) to assess liquidity risk, while long-term liabilities (e.g., bonds, mortgages) are key for understanding leverage. For firms in highly leveraged sectors like utilities or telecoms, managing these liabilities is crucial, whereas tech firms tend to rely less on debt financing and more on equity.

- Shareholder Equity: Shareholder equity represents the residual interest after liabilities are subtracted from assets. It’s a measure of the company’s net worth and includes components like common stock, retained earnings, and additional paid-in capital. A rising equity base typically indicates a company is retaining earnings or raising new capital, which could be a sign of financial strength or growth potential.

Assessing Leverage and Liquidity Risk

Evaluating a company’s balance sheet goes beyond understanding basic components. Analysts focus on key financial ratios to gauge the company’s liquidity and leverage:

- Liquidity: The company’s ability to meet its short-term obligations is assessed by ratios like the current ratio (current assets divided by current liabilities) or the quick ratio, which excludes inventory. A company with a low current ratio may face liquidity risks, particularly in sectors like retail or consumer goods, where cash flow fluctuations are common. Conversely, companies in sectors like pharmaceuticals or software often have stronger liquidity positions due to lower working capital needs.

- Leverage: Leverage risk assesses long-term financial stability. The debt-to-equity ratio (total liabilities divided by shareholder equity) measures leverage. Industries with high capital requirements, such as airlines or construction, often operate with higher leverage due to the need for debt-financed investments in infrastructure or equipment. In contrast, technology companies often maintain lower leverage ratios, relying more on equity financing to support growth.

Advanced Considerations: Asset Securitization and Hidden Liabilities

- Asset Securitization: In industries like financial services, asset securitization—where firms pool assets such as loans or receivables and sell them as securities—can be a significant factor. While this practice can provide liquidity, it can also mask off-balance-sheet risks, leading to a less transparent picture of the company’s leverage. For example, during the 2008 financial crisis, the overuse of securitized assets contributed to a severe underestimation of risk for major financial institutions.

- Hidden Liabilities: Analysts also scrutinize the balance sheet for potential hidden liabilities, such as underfunded pension plans, legal contingencies, or deferred taxes. These can pose significant risks if not accounted for properly. General Electric (GE), for instance, saw its stock price plummet in 2018 when investors discovered the extent of its hidden liabilities related to insurance and pension obligations.

- Lease Accounting: Recent changes in accounting standards, particularly IFRS 16 and ASC 842, now require companies to report operating leases on the balance sheet. This has been especially impactful for industries with substantial leasing obligations, such as retail and airlines. For example, when Delta Air Lines adopted IFRS 16, it saw a notable increase in reported liabilities due to the reclassification of leases, significantly affecting its leverage ratios.

Industry-Specific Balance Sheet Analysis

Different industries require distinct approaches to balance sheet analysis.

- Capital-Intensive Sectors: In industries like oil and gas, utilities, or automotive, companies typically have large asset bases with significant investments in fixed assets. Analysts focus on how well these firms manage long-term liabilities and capital expenditures, as poor management of these factors can lead to liquidity strains. For instance, BP faced substantial liquidity challenges after the Deepwater Horizon oil spill due to liabilities tied to environmental fines and clean-up costs.

- Tech and Service Industries: In contrast, tech firms like Apple or Microsoft often have lighter balance sheets, with fewer tangible assets and relatively low levels of debt. Here, analysts might focus more on intellectual property and cash reserves, which are key drivers of value in these sectors. The large cash reserves tech firms often maintain can provide a cushion during downturns or fund future investments.

By understanding the nuances of balance sheet interpretation across industries and taking into account regulatory changes, hidden liabilities, and sector-specific risks, analysts can make more informed assessments of a company’s leverage, liquidity, and overall financial health.

Income Statement Insights

The income statement provides crucial insights into a company’s financial performance, breaking down revenue, expenses, and profits over a specified period. EBITDA adjustments—especially normalization for non-recurring items and stock-based compensation—play a pivotal role in accurately assessing the profitability and operational efficiency of a business.

Revenue, Expenses, and Profits: The Basics

The income statement reveals three key elements:

- Revenue: The total income generated from the sale of goods or services. This “top line” is critical in assessing a company’s potential to grow and expand.

- Expenses: Expenses include both direct costs, such as Cost of Goods Sold (COGS), and operating expenses, such as salaries, rent, and utilities. Subtracting COGS from revenue gives gross profit, and deducting operating expenses from gross profit results in operating income, which indicates the company’s core operational performance.

- Net Income: After all expenses, taxes, and interest have been deducted from revenue, the remaining amount is net income, the “bottom line” of the income statement.

However, interpreting net income alone doesn’t always provide a clear picture of financial health, especially when companies engage in aggressive accounting practices or face one-off charges. This is where EBITDA adjustments come into play.

Understanding EBITDA Adjustments

Earnings Before Interest, Taxes, Depreciation, and Amortization (EBITDA) assess a company’s operational profitability in M&A valuation and financial modeling, as it excludes non-operating expenses and accounting decisions. To arrive at a normalized EBITDA, companies often make adjustments to reflect a more accurate picture of ongoing operations. Key adjustments include:

- Normalization for Non-Recurring Items: Companies may adjust for one-off charges, such as legal settlements, restructuring costs, or gains from asset sales. For instance, a manufacturing company may adjust its EBITDA to exclude expenses related to a major factory closure, ensuring these costs don’t distort future earnings estimates.

- Stock-Based Compensation: Tech companies, in particular, rely heavily on stock-based compensation for employee retention. While it’s a non-cash expense, it impacts profitability. Normalizing EBITDA to exclude stock-based compensation gives a clearer view of operational cash flow.

- Aggressive Revenue Recognition: Some companies recognize revenue early, inflating their income statements. This was seen in Tesla, which in recent years has reported significant revenue from the sale of regulatory credits. These credits are not part of its core automotive business but rather are one-time benefits from selling carbon offset credits to other manufacturers. By adjusting EBITDA to exclude these, analysts can better understand Tesla’s operational performance independent of these external factors.

Real-World Examples of EBITDA Adjustments

Several recent cases highlight the importance of EBITDA adjustments in understanding true financial performance:

- Tesla’s Regulatory Credits: Tesla has been notably aggressive in recognizing revenue from selling regulatory credits, which accounted for a substantial portion of its reported profitability in some quarters. These credits, while lucrative, are not a recurring aspect of its core business. By adjusting for these credits, analysts better evaluate Tesla’s underlying operational performance, which can look quite different without the benefit of these one-time gains.

- WeWork’s IPO: In 2019, WeWork famously adjusted its EBITDA by excluding a variety of expenses, including marketing costs, buildout expenses, and even community management costs. These aggressive adjustments were part of an attempt to present a rosier picture of its profitability ahead of its IPO, which ultimately collapsed as investors scrutinized the company’s high levels of ongoing expenses that couldn’t be reasonably classified as one-time.

- Uber’s Stock-Based Compensation: Uber’s early post-IPO earnings reports were heavily impacted by stock-based compensation, which was granted to employees as part of the company’s IPO process. Excluding this non-cash expense from its EBITDA allowed analysts to focus on Uber’s operational performance, but it also raised questions about its profitability and sustainability in the long run, as stock-based compensation remained a significant ongoing expense.

Industry-Specific EBITDA Adjustments

Different industries require distinct approaches when adjusting EBITDA, as the nature of non-recurring expenses, revenue recognition, and capital expenditures can vary widely:

- Tech Sector: In tech, stock-based compensation is a major adjustment. For instance, Google and Facebook regularly adjust for the millions of dollars in equity granted to employees. Without these adjustments, the companies’ net income figures would appear much lower, potentially distorting valuations.

- Retail and Manufacturing: In more capital-intensive sectors like retail or manufacturing, analysts often adjust for depreciation related to physical assets like stores or factories. Retailers like Macy’s may also adjust for store closure costs, providing a clearer view of ongoing profitability once underperforming assets are removed from the balance sheet.

- Energy Sector: Energy companies often face asset impairments related to changes in oil or commodity prices, and adjusting EBITDA for these one-off impairments provides a more normalized view of ongoing cash flows. For example, oil giant BP has adjusted its EBITDA following write-downs of oil field assets, giving investors a clearer picture of its operational health independent of commodity price swings.

Impact of Non-Recurring Charges on Income Statements

Non-recurring items like restructuring costs, legal settlements, or asset impairments skew net income if not adjusted. A notable example is General Electric (GE), which incurred significant one-off charges due to its restructuring efforts in recent years. Without adjusting for these costs, GE’s income statement would have painted an overly bleak picture of its profitability.

Another relevant case is Boeing, which faced substantial one-off charges related to the grounding of the 737 MAX aircraft. These charges heavily impacted the company’s profitability, but adjusting for them allowed analysts to focus on Boeing’s core business and its potential to recover once the crisis was resolved.

Advanced Cash Flow Statement Analysis: Free Cash Flow, Cash Flow Conversion, and Bankruptcy Indicators

A deeper understanding of the cash flow statement goes beyond simply reviewing cash inflows and outflows from operating, investing, and financing activities. For investors, analysts, and creditors, Free Cash Flow (FCF), cash flow conversion, and the insights these metrics provide assess a company’s ability to generate sustainable profits, meet debt obligations, and avoid financial distress. These factors also impact Discounted Cash Flow (DCF) models and evaluate the risk of bankruptcy.

Free Cash Flow (FCF) and Its Role in Valuation

Free Cash Flow (FCF) represents the cash a company generates after accounting for capital expenditures required to maintain or grow its asset base. FCF reflects the cash available for distribution to shareholders or for debt repayment, making it a central component in DCF models.

- Formula: FCF = Operating Cash Flow – Capital Expenditures

Investors and analysts often prefer FCF over net income because it is less susceptible to accounting manipulations and reflects the true liquidity available to the business. In DCF models, FCF projections are used to estimate a company’s intrinsic value by discounting future cash flows to present value. A company with a strong, predictable FCF is typically considered a stable investment, while a declining FCF may signal liquidity problems.

Cash Flow Conversion and Operational Efficiency

Cash flow conversion is another critical metric, calculated by dividing Operating Cash Flow (OCF) by Earnings Before Interest and Taxes (EBIT).

- Formula: Cash Flow Conversion = Operating Cash Flow / EBIT

A high conversion rate suggests that a company is efficiently turning its profits into cash, making it well-positioned to meet short-term liabilities or reinvest in its business. On the other hand, a low conversion rate points to issues with working capital management or aggressive revenue recognition practices, which may inflate earnings without generating corresponding cash inflows.

Predictors of Bankruptcy: Cash Flow and Debt Covenants

Cash flow plays a pivotal role in assessing a company’s financial distress risk. Debt covenants often include minimum FCF requirements or leverage ratios based on operating cash flows. Violating these covenants can lead to default, even if a company is profitable on paper. For instance, high capital expenditures (CapEx) that reduce FCF might put pressure on a company’s liquidity and its ability to meet covenants.

Cash flow analysis is also integral to models predicting financial distress, such as the Altman Z-score, a widely used predictor of bankruptcy that factors in metrics like operating income, market value, and liabilities. A company with consistently negative operating cash flow is at higher risk of breaching debt covenants or, in extreme cases, bankruptcy.

Real-World Cases: Cash Flow Issues and Financial Distress

Enron is one of the most infamous examples of cash flow manipulation masked by severe financial distress. In the early 2000s, Enron’s financial statements showed growing earnings, but its operating cash flow was significantly lower. The company used complex accounting schemes, such as hiding liabilities off-balance-sheet, to artificially inflate its reported earnings. Eventually, the discrepancies between reported profits and weak cash flows became evident, and the company collapsed, leading to one of the largest bankruptcies in history.

Another example is WorldCom, which used aggressive accounting tactics to boost its reported earnings while neglecting its deteriorating cash flows. The company capitalized billions of dollars in operating expenses, making its profits appear larger than they were. As WorldCom’s financial distress escalated, its inability to generate sufficient operating cash flow ultimately led to bankruptcy in 2002.

More recently, WeWork faced scrutiny for its high cash burn rate. While the company’s revenue was growing rapidly, its inability to generate positive free cash flow raised concerns about its sustainability. WeWork’s failed IPO highlighted the importance of focusing not just on top-line growth but also on the cash-generating ability of a business, especially when scaling quickly.

Strategic Insights from Cash Flow Statements

Analyzing a company’s cash flow can provide deeper strategic insights, especially when dissected by operating, investing, and financing activities:

- Operating Cash Flows: Consistent positive cash flow from operations is a strong indicator of a healthy business. A closer look at operating cash flows relative to reported net income can reveal potential earnings manipulation. Large discrepancies between the two may signal that a company is relying on accounting tactics, such as aggressive revenue recognition or capitalizing expenses, to inflate earnings.

- Investing Cash Flows: In industries with significant capital needs, such as oil & gas or manufacturing, high CapEx spending (outflows under investing activities) can indicate substantial growth investments. However, frequent asset sales or unusually high inflows in this section may suggest liquidity constraints or shifting business strategies to raise short-term cash. Companies like GE have often resorted to selling assets to shore up liquidity, a practice that can be a red flag for cash flow sustainability.

- Financing Cash Flows: In the financing section, large inflows from borrowing or equity issuance could indicate that the company is dependent on external capital to finance its operations. Significant debt repayments or dividend distributions, on the other hand, can highlight financial strength but must be supported by strong operating cash flows. For instance, AT&T has historically used a combination of debt financing and asset sales to manage its heavy capital expenditures and maintain its dividend policy, illustrating the delicate balance between financing strategy and cash flow management.

Equity and Earnings Per Share: Shareholders’ Equity Breakdown

Earnings per Share (EPS) is one of the most closely watched metrics in financial reporting, providing a snapshot of a company’s profitability on a per-share basis. However, a more sophisticated understanding of EPS requires analyzing diluted EPS, the impact of share buybacks, and how stock-based compensation or capital allocation strategies influence these figures. These factors not only affect a company’s per-share earnings but also reflect its approach to managing shareholder value and capital structure.

Diluted EPS and Its Importance

Diluted EPS accounts for the potential dilution of earnings caused by convertible securities such as stock options, convertible debt, or warrants. It provides a more conservative measure of a company’s profitability by including all possible shares that could be outstanding, thus offering a fuller picture of the impact on shareholders.

- The formula for Diluted EPS: Diluted EPS = (Net Income – Preferred Dividends) / (Weighted Average Shares Outstanding + Convertible Securities)

By incorporating stock options or other dilutive instruments into the calculation, diluted EPS shows what the EPS would be if all convertible securities were exercised. This metric is crucial for assessing the earnings quality, as it highlights the effect of potential share dilution on profitability.

Companies with significant stock-based compensation programs, such as tech firms like Apple or Microsoft, often report diluted EPS to give investors a clearer picture of the true earnings available to each share. For example, stock options granted to employees can substantially increase the number of shares, thus diluting EPS and reducing the perceived profitability on a per-share basis.

Share Buybacks and Their Effect on Earnings Metrics

Share buybacks (or share repurchase programs) are a common capital allocation strategy in which companies repurchase their own shares from the market, reducing the number of outstanding shares. This reduction can boost EPS even if a company’s net income remains flat, making the firm appear more profitable on a per-share basis.

- Effect on EPS: Since you calculate EPS by dividing net income by the number of shares outstanding, buybacks decrease the denominator, thus increasing EPS. While this can enhance shareholder returns in the short term, buybacks can also mask underlying issues with organic earnings growth if companies rely heavily on repurchases to inflate EPS.

A notable example is Apple’s extensive share buyback programs. Apple has spent over $400 billion on stock repurchases over the past decade, significantly reducing its outstanding shares and driving up its EPS. While these buybacks have returned substantial value to shareholders, they also highlight how capital allocation strategies can alter key financial metrics without corresponding increases in underlying profitability.

The Impact of Stock-Based Compensation on Dilution

Stock-based compensation, a popular method for incentivizing employees, particularly in high-growth sectors, introduces the potential for earnings dilution through the issuance of stock options or restricted stock units (RSUs). These forms of compensation are dilutive because they increase the number of shares outstanding when employees exercise their options, which lowers the EPS.

For instance, companies like Tesla and Amazon have large stock-based compensation packages, which often result in significant dilution over time. While these compensation structures can align employee incentives with company performance, they also reduce earnings per share for existing shareholders as more shares enter the market. This makes diluted EPS a more accurate indicator of the company’s profitability than basic EPS.

In some cases, the dilutive effect can be offset by share buybacks. Companies might use repurchase programs to counteract the dilution from stock-based compensation, effectively maintaining or even boosting EPS despite increased share issuance. However, this can also deplete cash reserves or lead to higher debt levels, raising concerns about the sustainability of such strategies.

Earnings Quality and Corporate Capital Allocation

Earnings quality evaluates a company’s financial health. While buybacks can enhance per-share metrics, they may obscure underlying challenges such as stagnant revenue growth or increased reliance on debt to fund repurchases. Additionally, aggressive share repurchase programs might limit a company’s ability to invest in growth opportunities, such as research and development or capital expenditures.

Conversely, if a company generates strong cash flows and has limited reinvestment needs, buybacks can be an effective way to return excess capital to shareholders. For instance, Microsoft successfully balanced share buybacks with significant investments in its cloud computing business, resulting in robust earnings growth and shareholder returns.

Real-World Cases: EPS Metrics and Corporate Actions

Several recent cases highlight the impact of dilution and buybacks on earnings metrics:

- Apple’s Buyback Program: Apple’s ongoing stock buyback program has dramatically reduced the number of shares outstanding, significantly boosting its EPS even in quarters where revenue growth was modest. In Q3 2023, Apple reported a 5% increase in EPS, driven largely by buybacks rather than operational performance. While this approach enhances per-share earnings, some analysts question whether Apple’s reliance on buybacks is sustainable in the long term.

- Tesla’s Dilution from Stock-Based Compensation: Tesla has faced notable dilution from its stock-based compensation plans. CEO Elon Musk’s compensation package, which includes substantial stock options, has contributed to a diluted EPS significantly lower than basic EPS. Despite Tesla’s impressive revenue growth, the dilution effect has been a point of focus for analysts, who consider the impact on long-term earnings quality.

- Netflix’s Impact of Options Dilution: In the tech sector, Netflix provides a strong example of how stock-based compensation affects EPS. In recent years, Netflix’s heavy reliance on stock options for employee compensation has diluted earnings significantly. The company’s diluted EPS is often lower than its basic EPS, underscoring the importance of considering dilution when evaluating earnings quality.

Accounting Principles and Standards

Understanding the differences between GAAP and IFRS, as well as how depreciation and amortization are handled, improves your ability to prepare transparent, reliable, and consistent financial statements.

GAAP vs. IFRS

Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP) and International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS) are the two dominant frameworks governing financial reporting across different regions. While GAAP is primarily used in the U.S., IFRS is adopted by over 120 countries, particularly in Europe and parts of Asia. These frameworks not only dictate how companies report their financial performance but also play a crucial role in valuation, especially during cross-border mergers and acquisitions (M&A). The convergence of GAAP and IFRS has long been a topic of debate, with significant implications for future financial reporting.

Sector-Specific Implications: Technology vs. Industrials

The differences between GAAP and IFRS can have varying impacts on different sectors, such as technology and industrial companies. These impacts are largely driven by how each framework approaches areas like revenue recognition, lease accounting, and asset valuation.

- Technology Sector:

In the tech industry, where intellectual property, intangible assets, and stock-based compensation are critical, IFRS and GAAP differ significantly in how these items are treated. Under GAAP, revenue recognition tends to be more rules-based and strict, particularly with multi-element arrangements, such as software licenses bundled with services, resulting in revenue being recognized over a longer time horizon under GAAP compared to IFRS. For example, a software company might report higher short-term revenue under IFRS, affecting its earnings profile, particularly during capital raises or M&A deals. - Industrials Sector:

For industrial companies, differences in lease accounting and inventory valuation can lead to material discrepancies between financial statements prepared under GAAP and IFRS. For example, IFRS does not allow the LIFO (Last In, First Out) method for inventory accounting, which is permissible under GAAP. This can affect the cost of goods sold (COGS) and, by extension, profitability metrics for industrial firms, especially those with significant raw material costs. Additionally, GAAP’s more prescriptive treatment of long-term leases (ASC 842) contrasts with IFRS 16, which requires all leases to be recorded on the balance sheet, potentially inflating liabilities for industrial companies with extensive leased machinery or facilities.

Impact of GAAP vs. IFRS on Cross-Border M&A

The choice of accounting standards becomes particularly important in cross-border M&A deals, where differences between GAAP and IFRS can materially affect valuation, deal structuring, and post-acquisition integration. Discrepancies in how revenue, expenses, and assets are recorded can lead to challenges in reconciling financial statements, ultimately influencing how both parties view the target company’s value.

One notable example is the 2017 ABB and GE Industrial Solutions deal, where ABB (a Swiss company using IFRS) acquired GE’s Industrial Solutions (an American company using GAAP) for $2.6 billion. The differences between the two accounting frameworks required careful adjustments during the valuation process:

- Revenue Recognition: GE’s use of GAAP meant stricter rules for revenue recognition, particularly for long-term contracts. Under IFRS, ABB’s more judgment-based approach allowed for earlier revenue recognition, creating disparities in earnings expectations. Adjusting for these differences was crucial to aligning the valuation models.

- Asset Valuation: GAAP’s treatment of certain long-term assets, such as property, plant, and equipment (PPE), tends to be more conservative compared to IFRS, which allows revaluation. This difference led to a divergence in asset values between the two companies, influencing ABB’s assessment of the value of GE’s fixed assets.

- Post-Acquisition Adjustments: Following the acquisition, ABB had to reconcile GE’s GAAP-based financials to IFRS for consolidated reporting, resulting in significant adjustments. These included recalculations of long-term liabilities and lease commitments, which affected the post-acquisition financial statements.

Convergence and Future Financial Reporting

Efforts to converge GAAP and IFRS have been ongoing for years, with significant progress made in areas like revenue recognition (ASC 606/IFRS 15) and lease accounting (ASC 842/IFRS 16). However, full convergence remains elusive, with persistent differences in key areas like financial instruments, goodwill impairment, and inventory accounting.

As cross-border transactions continue to rise, companies are likely to encounter increased pressure to adopt or at least reconcile with IFRS to facilitate smoother deal-making processes. For example, the IFRS 9 standard on financial instruments differs from GAAP’s ASC 320, particularly in the treatment of loan loss provisions and impairment models. These differences are significant for financial institutions or any company with a large loan portfolio, potentially impacting their risk assessment and valuation in M&A scenarios.

Depreciation and Amortization

Depreciation refers to the allocation of the cost of tangible assets over their useful lives. In GAAP, common methods include straight-line, declining balance, and units of production. IFRS also allows similar methods but emphasizes reflecting the pattern of economic benefits derived from the asset.

Amortization concerns intangible assets like patents and goodwill. Both GAAP and IFRS require systematic allocation over the useful life of the intangible asset, but differences may arise in estimated useful lives and residual values.

Consistency in these practices affects the transparency and reliability of financial statements, making it important for companies to understand and correctly apply these principles. Transparent depreciation and amortization methods enhance investor confidence and ensure that financial reports remain consistent and reliable.

Financial Statement Presentation and Analysis

The next section focuses on the essential aspects of preparing and presenting financial reports and exploring the tools and techniques needed for effective financial analysis.

Preparing and Presenting Financial Reports

When preparing and presenting financial reports, it is crucial to ensure the accuracy and completeness of the data. Financial reporting encompasses the collection and presentation of current and historical data to inform stakeholders about a company’s financial health.

Annual reports must include comprehensive details, such as income statements, balance sheets, and cash flow statements. These financial statements must be audited to guarantee their credibility and reliability. Key financial ratios, such as the quick ratio, provide deeper insights by assessing liquidity and financial stability.

The disclosed information should adhere to accepted accounting practices and standards, maintaining transparency with investors. Efficient presentation tools, such as tables and charts, make data easily interpretable for better decision-making.

Tools and Techniques for Financial Analysis

Analyzing financial statements requires robust tools and methodologies to extract meaningful insights. Ratios like return on equity (ROE) and debt-to-equity ratio help in assessing profitability and leverage.

Techniques such as trend analysis and comparative analysis allow us to identify growth patterns and compare performance against industry benchmarks. Using case studies as examples, we can illustrate the effective application of these tools. It’s also vital to consider both quantitative and qualitative aspects during analysis.

Modern software tools streamline the financial statement process, making the presentation more efficient and accurate. These tools also aid in forecasting and scenario analysis, enhancing strategic planning.

Detailed Analysis of Financial Statements

Understanding the nuances of financial statements reveals valuable insights about a company’s performance. You can form a comprehensive view of a company’s financial health by scrutinizing sections like the Management Discussion and Analysis (MD&A), Audit Opinion, and Key Financial Ratios.

Management Discussion and Analysis (MD&A)

The MD&A offers a narrative explanation of the financial statements from the perspective of the company’s management. This section provides context about the financial results, discussing factors that influenced performance, both positively and negatively. Typically, it encompasses operational highlights, trend analysis, and future outlook.

We should pay particular attention to:

- Revenue trends and operational costs.

- Management’s expectations for future performance.

- Known risks and uncertainties.

Accurate MD&A allows investors to gauge the reliability and future prospects of the company.

Audit Opinions and Their Implications

An audit opinion offers insights into the accuracy and reliability of a company’s financial statements. Professional analysts pay close attention to these opinions as they reflect the integrity of a company’s financial reporting and can significantly influence investment decisions. There are four primary types of audit opinions, each with different implications for stakeholders:

- Unqualified Opinion: An unqualified opinion indicates that the financial statements are presented fairly in all material respects in accordance with applicable accounting standards. An unqualified opinion enhances confidence in the company’s financial data and usually signals strong internal controls and reliable financial reporting.

- Qualified Opinion: A qualified opinion suggests that, while most of the financial statements are accurate, there are exceptions or deviations from accounting standards. These issues may not be severe enough to render the entire report unreliable, but they warrant further investigation. Qualified opinions can be early warning signs of underlying problems that may not yet be fully reflected in the financials.

- Adverse Opinion: An adverse opinion indicates that the financial statements are materially misstated or do not comply with generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP) or International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS). An adverse opinion is a strong red flag, often signaling deep-rooted financial or operational issues that could lead to future financial distress or even insolvency.

- Disclaimer of Opinion: When an auditor is unable to provide an opinion due to insufficient evidence or access to information, a disclaimer is issued. This suggests serious concerns about the company’s transparency and ability to provide accurate financial data. A disclaimer often leads to heightened scrutiny from regulators and investors alike.

Responding to Qualified or Negative Audit Opinions

Professional analysts must approach qualified, adverse, or disclaimed audit opinions with caution, as these can serve as early indicators of financial instability. While a qualified opinion may point to isolated issues, such as a specific accounting treatment or disclosure inadequacy, it still raises questions about the overall health of the company’s governance. Material weaknesses in internal controls or deviations in reporting practices could precede more significant financial difficulties if left unaddressed.

Analysts should investigate the root causes of any qualified opinions or material weaknesses, looking beyond surface-level explanations. Red flags such as aggressive revenue recognition, off-balance-sheet liabilities, or unusual accounting treatments may point to systemic issues that could impair long-term financial performance.

Notable Cases of Qualified Opinions and Financial Distress

Several high-profile cases demonstrate how negative audit findings can precede financial collapse:

- Lehman Brothers (2008): Leading up to its bankruptcy, Lehman Brothers received qualified opinions regarding the firm’s use of Repo 105 transactions, which artificially inflated its balance sheet by moving debt off its books. Despite these warnings, the firm continued to engage in risky financial practices, culminating in one of the largest financial collapses in history. Qualified audit opinions highlighted weaknesses that analysts should have scrutinized more closely.

- Parmalat (2003): The Italian dairy company Parmalat received several qualified opinions due to discrepancies in its cash accounts and the overstatement of assets. These warnings were ignored until the company’s massive €14 billion fraud was uncovered, leading to its eventual collapse. This case illustrated how auditors’ concerns over material misstatements should have triggered more intense scrutiny from investors and analysts.

- Lehman Brothers and Parmalat both show how seemingly isolated issues can cascade into broader financial failures when audit concerns are not addressed.

Best Practices for Analysts

- Detailed Analysis of Audit Opinions: Analysts should dissect audit reports to understand the scope of exceptions in qualified opinions. Identifying recurring issues, such as revenue recognition inconsistencies or undisclosed liabilities, can help forecast future risks.

- Monitoring Material Weaknesses: If an audit reveals material weaknesses, especially in critical areas like internal controls or financial reporting, these should be viewed as serious threats to financial stability. Analysts should factor these into their financial models and valuations.

- Cross-Referencing with Financial Metrics: Qualified or adverse opinions should be examined alongside financial metrics like free cash flow and debt-to-equity ratios. A company with a qualified opinion and declining liquidity ratios may be a candidate for further scrutiny or even potential bankruptcy.

- Learning from History: Understanding cases like Enron, Lehman Brothers, and Parmalat allows analysts to recognize the red flags that precede financial distress. The role of auditors in surfacing these issues is critical, but it is up to analysts and investors to interpret and act on this information appropriately.

Key Financial Ratios

Financial analysis goes beyond basic ratios by incorporating advanced metrics that provide a deeper understanding of a company’s value creation, capital efficiency, and risk profile. These ratios are critical for assessing the financial viability of corporations, especially in the context of corporate valuations, mergers and acquisitions (M&A), and leveraged buyout (LBO) models.

1. Return on Invested Capital (ROIC)

ROIC measures how efficiently a company uses its invested capital to generate profits, providing a clear picture of how well management allocates resources. The formula for ROIC is:

Invested capital typically includes both equity and debt, giving a comprehensive view of a company’s capital usage.

- Why it matters: ROIC helps you understand a company’s ability to generate value beyond its cost of capital. Investors often benchmark ROIC against the Weighted Average Cost of Capital (WACC) to determine if the company is creating or destroying value. A company with an ROIC higher than its WACC is typically considered to be adding value for shareholders.

- Case Study: Berkshire Hathaway, under Warren Buffett’s leadership, consistently seeks companies with high ROIC for acquisitions. Buffett emphasizes businesses that generate strong returns on invested capital, as this indicates sustainable competitive advantages. One high-profile example is Berkshire’s acquisition of Precision Castparts in 2016. Precision Castparts had a historically high ROIC, which Buffett viewed as a critical factor in its long-term profitability and growth potential.

2. Weighted Average Cost of Capital (WACC)

WACC represents the average rate that a company is expected to pay its investors (both equity and debt holders) to finance its assets. It accounts for the proportion of equity and debt in the company’s capital structure. The formula is:

Where:

- EEE = Market value of equity

- DDD = Market value of debt

- Why it matters: WACC plays a fundamental role in corporate valuations, particularly in Discounted Cash Flow (DCF) models, where it is used as the discount rate to estimate the present value of future cash flows. A company’s ability to generate returns greater than its WACC is indicative of value creation, making it attractive to investors and acquirers.

- Case Study: In 3G Capital’s acquisition of Heinz, the private equity firm assessed Heinz’s ability to generate cash flows above its WACC. By aggressively cutting costs and improving operational efficiency, 3G Capital boosted Heinz’s ROIC, ensuring the investment would provide substantial returns above the company’s WACC.

3. EBITDA and Debt Metrics in LBO Models

In leveraged buyouts, companies are often acquired using a significant amount of debt financing, which puts a premium on metrics like EBITDA and Debt/EBITDA ratios. EBITDA (Earnings Before Interest, Taxes, Depreciation, and Amortization) serves as a proxy for cash flow available to service debt, making it a critical metric for assessing a company’s ability to meet debt obligations post-acquisition.

- Debt/EBITDA: This ratio is used to assess a company’s leverage by comparing its debt load to its ability to generate cash flow. A higher ratio suggests increased financial risk, while a lower ratio indicates stronger debt servicing capacity.

- Why it matters: In LBO models, acquirers typically load a target company with debt to finance the purchase. Monitoring the Debt/EBITDA ratio ensures that the target company can generate enough cash flow to cover interest payments and eventually reduce the debt burden.

- Case Study: The 2007 Blackstone acquisition of Hilton Worldwide provides a notable example of using debt metrics in LBOs. Blackstone relied heavily on the company’s EBITDA growth projections to justify the large debt financing of the deal. Despite initial challenges during the global financial crisis, Hilton’s strong EBITDA growth and cash flow conversion allowed the company to successfully deleverage and eventually go public again in 2013, resulting in a lucrative exit for Blackstone.

4. Cash Flow Metrics and Bankruptcy Prediction

Metrics like Free Cash Flow (FCF) and cash flow conversion are not only used for valuation but also as predictors of financial distress. FCF represents the cash a company generates after accounting for capital expenditures and is a key determinant of a company’s ability to repay debt, fund operations, or return capital to shareholders.

- Altman Z-Score: Developed by Edward Altman, this score combines several financial metrics, including working capital, retained earnings, EBIT, and market value of equity, to predict the likelihood of bankruptcy. A low Z-Score indicates higher bankruptcy risk.

- Why it matters: Cash flow problems often precede financial distress. Negative FCF or poor cash flow conversion rates can indicate liquidity issues that may lead to solvency concerns. Analysts closely monitor FCF to assess the long-term financial health of a company.

- Case Study: The downfall of Enron is a famous example of cash flow issues preceding bankruptcy. Despite reporting high earnings, Enron’s cash flow from operations was consistently negative due to aggressive revenue recognition and off-balance-sheet transactions. By analyzing the discrepancies between Enron’s reported earnings and its cash flow, analysts could have predicted the financial disaster that unfolded in 2001.

Practical Applications

Practical applications of public company financial statements include investment analysis, credit analysis, and strategic planning. These areas utilize financial statements to assess various dimensions of a company’s performance and potential.

Investment Analysis

Investment analysis relies heavily on the financial statements of public companies. Investors use these documents to evaluate profitability, cash flow, and overall financial health.

Key metrics include:

- Earnings Per Share (EPS): Indicates the company’s profitability.

- Price-to-Earnings (P/E) Ratio: Assesses the company’s stock value relative to its earnings.

- Return on Equity (ROE): Measures financial efficiency.

Income statements, balance sheets, and cash flow statements serve as critical tools in identifying viable investment opportunities. For instance, Business Analysis and Valuation highlight the importance of forecasted financial statements in investment decisions.

Credit Analysis

Creditors utilize financial statements to determine the creditworthiness of public companies. This process primarily involves assessing liquidity, leverage, and cash flow adequacy.

Key metrics include:

- Current Ratio: Evaluates short-term financial stability.

- Debt-to-Equity Ratio: Assesses the level of financial risk.

- Interest Coverage Ratio: Measures the company’s ability to meet interest payments.

Strategic Planning

Financial statements are not just tools for tracking a company’s performance; they are integral to corporate strategy, influencing critical decisions on capital allocation, divestitures, and acquisitions. By evaluating financial ratios and metrics, management can make informed decisions about where to invest, how to manage resources, and when to pursue mergers or sell off underperforming assets.

1. Capital Allocation

Capital allocation is one of the most important strategic decisions a company’s management faces. It involves determining how to deploy available resources to generate the highest possible returns for shareholders. Financial statements provide the foundation for these decisions by offering insights into a company’s profitability, cash flow, and return on capital.

- Financial Ratios for Decision-Making: Management frequently uses ratios like Return on Equity (ROE), Return on Invested Capital (ROIC), and Free Cash Flow (FCF) to assess whether it’s more strategic to reinvest in the business, return capital to shareholders through dividends or share buybacks, or invest in external opportunities.

- Example: Apple’s share buyback program is a prime example of capital allocation driven by financial analysis. By generating strong cash flows, Apple has been able to return billions to shareholders while still investing in R&D and expanding its product portfolio. The company’s financials—particularly its FCF and profitability—allow it to make these balanced capital allocation decisions.

2. Divestitures

Companies often decide to divest underperforming or non-core assets based on insights from financial statements. The goal of divestitures is to streamline operations, reduce debt, or generate cash to reinvest in more profitable areas.

- Key Financial Metrics: Metrics such as EBITDA margins, asset turnover, and return on assets (ROA) can reveal when certain segments are underperforming or consuming too much capital relative to their contribution to the company’s overall performance.

- Example: In 2018, General Electric (GE) announced plans to divest its transportation and healthcare divisions to focus on its core industrial businesses. The decision followed years of declining profitability in these units, as revealed in the company’s financial reports. This divestiture was part of GE’s strategy to strengthen its balance sheet and improve its cash flow position.

3. Acquisitions and Mergers

Acquisitions are a strategic tool for driving growth, entering new markets, or gaining competitive advantages. The decision to acquire a company is based on extensive financial modeling, which includes analysis of the target company’s balance sheet, income statement, and cash flow.

- Strategic Financial Ratios: In an M&A scenario, management often looks at metrics like the debt-to-equity ratio, P/E ratio, and ROIC of the target company. These ratios help determine whether the acquisition will add value or burden the company with excess debt or integration challenges.

- Example: Disney’s acquisition of 21st Century Fox in 2019 highlights how financial modeling feeds into strategic decisions. Disney used financial projections and valuation models to evaluate Fox’s cash flows, assets, and earnings potential. The deal, valued at over $71 billion, was structured based on the expectation that Fox’s content library and international presence would enhance Disney’s streaming strategy and generate long-term revenue growth.

4. Financial Modeling in M&A

During the M&A process, financial modeling plays a pivotal role in determining whether a deal makes strategic sense. This modeling typically involves building Discounted Cash Flow (DCF) models and analyzing key ratios like WACC and ROIC to assess whether future cash flows justify the acquisition price.

5. Risk Management and Long-Term Strategy

Beyond day-to-day decisions, financial statements also guide long-term corporate strategy, helping management assess financial risks and opportunities for growth. For instance, financial data can signal the need for investment in new technologies, expansion into new markets, or, conversely, cutting back on certain expenditures due to tightening margins.

Empowering Bank Investment Analysts

While a comprehensive understanding of public company financial statements is essential for bank investment analysts, it’s important to recognize that this analysis is just one component of a broader investment strategy. Delving into the intricacies of the balance sheet, income statement, and cash flow statement can provide valuable insights into a company’s financial health.

Metrics such as free cash flow and earnings per share are instrumental in shaping strategic investment decisions. However, these financial metrics should be cross-checked with qualitative factors, such as market sentiment analysis, industry trends, and macroeconomic indicators, to form a holistic view. Additionally, considering risk assessments alongside financial analysis will enhance your ability to identify opportunities and mitigate potential risks in a dynamic market landscape. For further development of your analytical skills and to gain deeper insights, explore Daloopa’s suite of tools and resources. Our platform offers advanced analytical capabilities and real-time data to support informed decision-making. Sign up today and elevate your financial analysis approach! Contact us for more information.